Wittgenstein after the Eleventh

Today’s post is part of University Press Week’s blog tour, which celebrates how university presses amplify voices, disciplines, and communities.

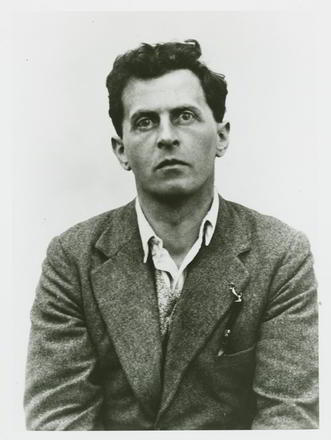

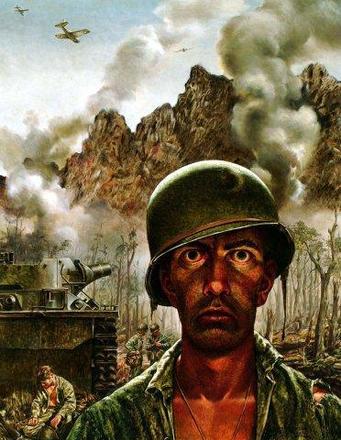

I cannot help it: whenever I look at the well-known photograph of Ludwig Wittgenstein taken in 1929 right after he was awarded a scholarship by Trinity College, I invariably see in his eyes the “thousand-yard stare”—an expression apparently coined by the US Marines to refer to the blank, unfocused, dissociated look of the soldier who has been deeply affected by the horrors of warfare. A veteran himself of the Great War, Wittgenstein in that photograph is ostensibly not looking at the camera. His gaze is as blank and numbed as I imagine his train of thought to be. The subtly distinct direction taken by each eye produces a disturbing effect, while the pursed lips with their downturned corners suggest melancholy. All this, together with the slightly dishevelled hair, reinforces the dissociation and emotional detachment expressed in the philosopher’s thousand-yard stare. This is a photograph of a man who has seen everything and is now absent-mindedly contemplating nothingness.

Among other assignments that he undertook during the war, between March and June 1916 Wittgenstein served as a field artillery observer on the eastern front during the Brusilov Offensive, in which the Austrian army incurred heavy casualties. In his geheime Tagebücher, or “secret journals,” he repeatedly expressed his fear of dying. Although Wittgenstein returned from the war practically unscathed physically (his only wounds were caused by an accidental explosion at the army workshop where he worked for several months), it is fair to speculate that the war left an indelible emotional mark on him. In fact, his baptism of fire drastically altered his philosophical meditations, which up to then had been strictly concerned with logic. After witnessing combat, Wittgenstein started to write in his journal thoughts on the meaning of life, on God, on ethics—a radical change in his philosophical reflections that would be transposed into the last two sections of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921). To be sure, there is no hard evidence to support the hypothesis that Wittgenstein suffered from moral wounds or what at the time was known, in Great Britain, as shell shock (Freud called it “war neurosis”). Nonetheless, the sudden change in his thinking from logical matters to moral philosophy and mysticism, together with that uncanny photograph, suggest that the experience of modern warfare had a profound impression on Wittgenstein’s psyche. Indeed, the Great War did affect Wittgenstein in important ways.

If my interpretation of the photograph is correct, Ludwig Wittgenstein’s thousand-yard stare would place the philosopher among the casualties of the Great War. The mass butchery perpetrated in that conflict left ten million troops dead out of the sixty-five million who had been mobilized to fight. Eight million others returned permanently disabled. An unknown number of soldiers (Wittgenstein perhaps among them) went home suffering from shell shock or moral wounds. Homecoming would not be easy for many veterans. War is a life-changing event that routinely injures the body, the mind, and the moral sense of soldiers. Troops die or are severely wounded even in favourable circumstances. Soldiers are expected to perform what in civilian society is morally repugnant and legally prosecuted—injuring, killing, laying waste to conditions that make the world livable; their duties often consist of undertakings that radically contravene their most profoundly seated ethical convictions. Furthermore, they may feel betrayed by their superiors, used by politicians, or misunderstood by family and friends. Feelings of remorse, grief, shame, trauma, meaninglessness, and resentment, as well as self-loathing, loss of trust in people, and a general sense of alienation are the lot of many veterans. A high number of former combatants are haunted by the horrors they have lived and by memories of the dead—of the men they have killed, of the comrades they have seen die. Once reintegrated into civilian society, veterans constitute haunting legacies; they are reminders of political decisions that led to lethal action, reminders of a world ruled by a logic of its own, reminders of abjection, of the unspeakable. For all these reasons, the veteran’s homecoming is fraught with problems. In this context, I wonder if Wittgenstein’s somewhat erratic personal and professional life after being released from Italian captivity in the summer of 1919 until his return to Cambridge in 1929 has to do with the usual troubles experienced by many demobilized veterans.

Literature has portrayed the difficulties that veterans of the Great War endured in their adaptation to civilian life. For them, home could become a foreign land. Works such as Rebecca West’s pioneering The Return of the Soldier (1918), Bertolt Brecht’s play Drumming in the Night (1922), Ernst Toller’s expressionist dramas The Transformation (1919) and Hinkemann (1923), Laurence Stallings’s Plumes (1924), Joseph Roth’s Hotel Savoy (1924), William Faulkner’s Soldiers' Pay (1926), and Erich Maria Remarque’s The Way Back (1931) show the hardships experienced by Great War veterans during this time of transition. Artworks by Otto Dix (e.g., Skin Graft [1924], The Skat Players [1920]) and George Grosz (e.g., Grey Day [1921]), as well as the photographs of gueules cassées, or “broken faces,” included in Ernst Friedrich’s War against War (1924) depict a social landscape populated by severely disabled veterans. Marital troubles, joblessness, social maladjustment, chronic health issues, prosthetic bodies, severe mental illnesses, political rebellion, the feeling or the fact of being misunderstood and mistreated by society, as well as the self-awareness of having been decisively transformed by the war are all elements that are present in those works.

The photograph of Wittgenstein seems to whisper, too, new ways for commemorating Remembrance Day and the centennial of the Armistice of 11 November 1918. After all, Wittgenstein cuts the perfect image of a transnational individual: on one hand he fought in the Austrian army; on the other he lived in Britain for many years. One century after the warring forces signed the Armistice, we would make an ethically meaningful gesture by directing remembrance not only to those who fell in the battlefield, but also to those who survived the war but became someone else as a result of the extreme experience of combat. As individuals, we could make of the Eleventh of November of 2018 an inclusive day of remembrance and homage addressed to everyone—to the fallen from every single country that participated in the war of 1914–18, as well as those who physically, psychologically, or morally suffered because of the conflict. Furthermore, it should not be forgotten that the Armistice did not alleviate the dire predicament of German civilians. Britain did not lift its blockade on food exports to Germany until January 1919, and restrictions on food to the Germans would be kept in place until July 1919. On Remembrance Day we must bear in mind that many German civilians died of hunger during the months that followed the Eleventh Hour of the Eleventh Day of the Eleventh Month of 1918.

Together with the men fallen in the line of duty, all those victims of the Great War (e.g., traumatized veterans, disabled ex-soldiers, civilians trapped and killed or wounded in war zones, men, women, and children who died of hunger after 11 November 1918) regardless of their country of origin, should be remembered in our commemoration of the centennial of the Armistice of 1918. In our globalized world, true remembrance needs to transcend the boundaries of the nations and overcome the logic of confrontation. In the past, Remembrance Day has been mostly a day of communal grieving and national self-affirmation. From now on, it could also be a day of transnational mourning, communion, and solidarity.

Image 1: Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1929

Image 2: Tom Lea, Two-Thousand-Yard Stare, 1944

Nil Santiáñez is a professor of Spanish and International Studies at Saint Louis University. He is the author of Topographies of Fascism, Goya/Clausewitz, Investigaciones literarias, Ángel Ganivet: Una bibliografía anotada (1892–1995), De la Luna a Mecanópolis, and Ángel Ganivet, escritor modernista. His most recent book, Wittgenstein’s Ethics and Modern Warfare, was published with WLU Press in October.

Today’s post is part of University Press Week’s blog tour, which celebrates how university presses amplify voices, disciplines, and communities. Day 4 of UP Week includes blog posts by our colleagues at:

University of California Press

University of Nebraska Press

University of Alabama Press

Rutgers University Press

University of Rochester Press

Beacon Press

University Press of Kansas

Harvard University Press

University of Georgia Press

University of Toronto Press

MIT Press