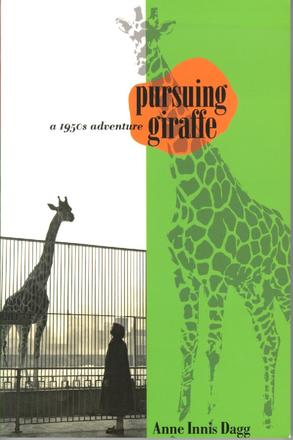

Pursuing Giraffe

A 1950s Adventure

Description

In the 1950s, Anne Innis Dagg was a young zoologist with a lifelong love of giraffe and a dream to study them in Africa. Based on extensive journals and letters home, Pursuing Giraffe vividly chronicles the realization of that dream and the year that she spent studying and documenting giraffe behaviour. Dagg was one of the first zoologists to study wild animals in Africa (before Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey); her memoir captures her youthful enthusiasm for her journey, as well as her näiveté about the complex social and political issues in Africa.

Once in the field, she recorded the complexities of giraffe social relationships but also learned about human relationships in the context of apartheid in South Africa and colonialism in Tanganyika (Tanzania) and Kenya. Hospitality and friendship were readily extended to her as a white woman, but she was shocked by the racism of the colonial whites in Africa. Reflecting the twenty-three-year-old author’s response to an “exotic” world far removed from the Toronto where she grew up, the book records her visits to Zanzibar and Victoria Falls and her climb of Mount Kilimanjaro. Pursuing Giraffe is a fascinating account that has much to say about the status of women in the mid-twentieth century. The book’s foreword by South African novelist Mark Behr (author of The Smell of Apples and Embrace) provides further context for and insights into Dagg’s narrative.

Reviews

"This book is. ..about one person's intellectual imagination, spirit of adventure, and daring: where she has long dreamed of going, where others either say she shouldn't or cannot go, and some work against her going, she goes. ...Anne Innis Dagg has written a brave and moving account of her time as a young white woman travelling and doing research in Southern and East Africa. "

- Mark Behr, author of The Smell of Apples and Embrace

"Dagg . .. learned a great deal about giraffe . .. but those studies are among the least significant reasons for reading this wonderful memoir . .. Instead it should be read because it's an engaging, amusing, thoughtful, charming, honest, probing and eye-opening account of a young Canadian woman's encounters with racism, with sexism, with colonialism and with the animal kingdom in general and people in particular--especially men. ... Dagg is a natural story-teller. "

- Jon Fear, The Record (Kitchener), March 10, 2007

"This beautifully written book explores a young Canadian biologist's field studies on giraffes, and her impressions of Africa and its people in the mid-1950s. But her story is much more than just research into giraffe behaviour and life in Africa. Anne Innis Dagg is most concerned about what she learned, while in Africa, about herself. Pursuing Giraffe relates the tale, through stories of giraffes and the evolving situation within Africa, of a brave person's effort to live life honestly . .. travelling alone, pursuing zoological research at a time when work in the field was not only rare but also totally male-driven. ... One cannot forget when reading Pursuing Giraffe that its bones rest on a journal that had been kept over 1956 and 1957, and the immediacy of that journal is one of the book's most powerful attributes. "

- Margaret Derry, University of Toronto Quarterly, Letters in Canada 2006, Volume 77, Number 1, Winter 2008