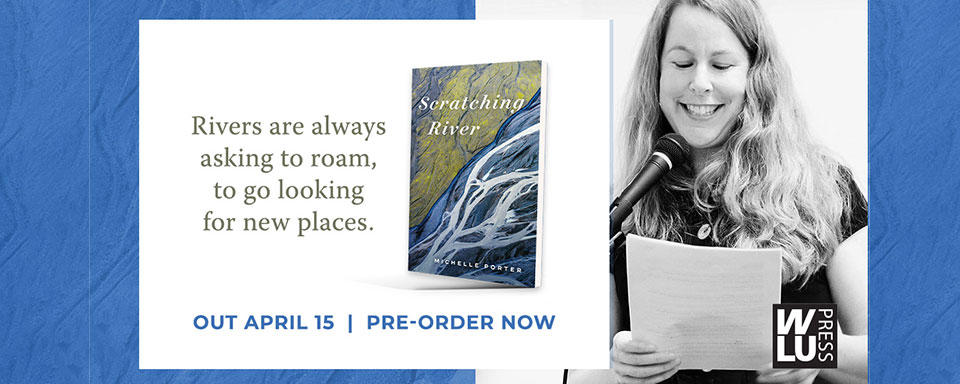

Q&A with Michelle Porter, Scratching River

Clare Hitchens, our Sales and Marketing Coordinator, sat down with Michelle Porter to ask her some questions about Scratching River and her writing process. In this first post, Clare asks Michelle about how the intent of the book shifted from the original and how the point of view was important in telling the story.

CH: You’ve said that you did not set out to write about your brother. What was the story you originally intended to tell and how did it shift?

MP: I’d planned to write in conversation with a Métis ancestor, Louis Goulet, whose memories had been recorded in a book. I set out to write a creative response to his travels across the prairie homeland and the beauty of the landscape. I wanted to write about the past, present and future Métis relationship with the land. I did write that story, but I braided my brother’s story around it. In a way I think this is because geography is personal. As I was reading about and following along Louis Goulet’s travels and movements across the homeland—reading his evocative descriptions of red river cart movement across the prairies—I experienced physical body memories of my own travels as a child. Only instead of being in a Red River cart, I was in a car, and we were going to see my brother. The rhythms in these travels were indelibly connected to our travels and to the resilience of our people, the Métis. I recall a moment when I felt the 14-year-old girl I was sit down beside me and say, I have a story to tell. What could I do? I had to tell it. The story she wanted to tell was about her older brother. My brother is autistic and schizophrenic, twin diagnoses that made his behaviour so challenging my mother placed him in a home for children with his range of mental disabilities. He thrived in that home. When he turned 18 (and I was 14) my mother had to find a home for her adult son — he couldn’t stay at the children’s home. She found what she thought was a beautiful ranch for him to live in — but it turned out to be a place where my brother experienced severe injury and hospitalization and was in the newspapers for suspected abuses and investigations. This is the story of how that 14-year-old and her brother survived it in different ways.

CH: The use of second person narrative in the portions where you recall your brother’s story is interesting. How did you land on that as a way to tell the story?

MP: It was all about relationality. I didn’t want to take on an authoritative voice at all or have the book be all about my own perspective. I wanted the book to be relational and the use of the second person allowed the book to be about the relationship with my sister, who is obliquely the “you” referred to, but also to the reader who gets pulled into the narrative in a more intimate way. In this way I am saying this story is mine and it is also yours — let’s carry it together.

There’s another aspect, too. I wanted this book to follow in the heels of Métis storytelling traditions and ways of relating and the use of the second person makes parts of the book a conversation with my sister and the reader. My brother can’t speak and so he couldn’t tell me his story and so the way to build the “all my relations” ethic in this book was to reach outward in conversation with my sister and to offer my mother’s words as well. In this way, I am de-centring myself and telling my brother’s story as a constellation of his relations. I think he’d tell me he loved that, if he could speak.